Have you noticed that some New Testament verses are missing in modern Bible translations like the NIV, ESV, or NLT? Are you familiar with the King James Version Only (KJVO) movement? While I don’t fully align with their position on the KJV, I now understand why they hold such views and want to share what I’ve learned in this essay.

Let me be clear: I’m not questioning the authority of Scripture. Whether based on the Critical Text (CT) or the Textus Receptus (TR), the Bible we have today is the inspired Word of God—sufficient for salvation and equipping us for every good work (2 Timothy 3:16-17). However, the historical and textual decisions that shaped our modern Bibles merit closer attention. Understanding these differences can deepen our appreciation for God’s preservation of His Word and help us make informed choices about which translation to read, study, and memorise.

Manuscript Traditions: The Key to the Differences

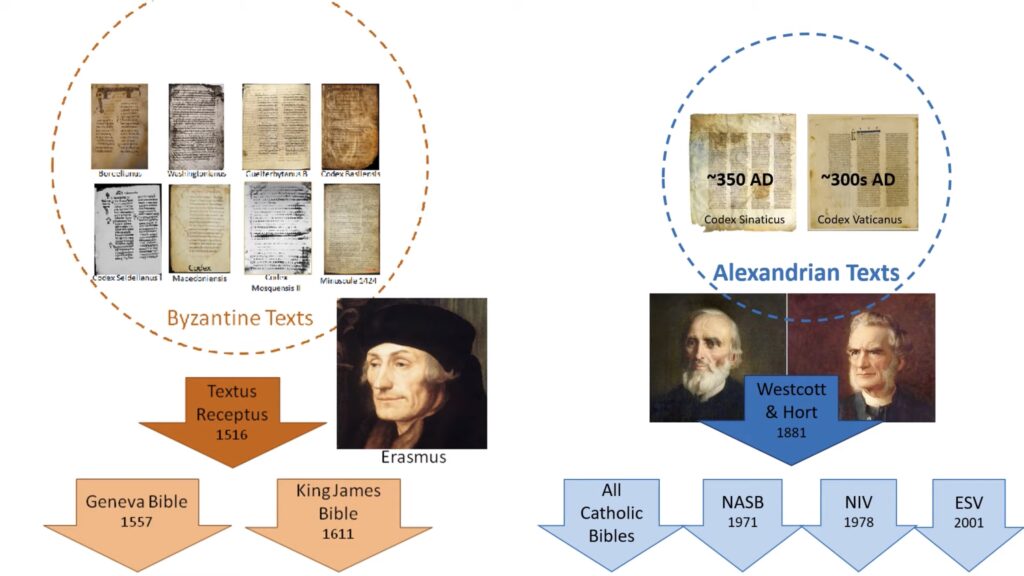

- Textus Receptus (TR) – Based on the Byzantine manuscript tradition (the traditional text of the Greek-speaking churches), compiled by Erasmus in 1516 and used in the KJV and NKJV.

- Critical Text (CT) – Based on the Alexandrian or Egyptian tradition, preferred by modern scholars and used in most contemporary translations; if it’s not KJV or NKJV, then your Bible is mostly likely based on CT manuscript. It is revised regularly through the Nestle-Aland (NA) line (28th ed. as of 2012).

Major Omissions in Modern Translations

Most differences between these traditions are minor—like whether a phrase reads “Jesus Christ” or “Christ Jesus.” However, some variations significantly affect meaning. Consider these key passages omitted in the Critical Text tradition:

- The Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:13) – The phrase “For Yours is the Kingdom and the power and the glory forever. Amen” is entirely missing in CT-based versions, even though it is part of every Christian’s prayer when they pray the Lord’s prayer.

- Post-resurrection appearances (Mark 16:9-20) – The longer ending of Mark, which includes Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances and the Great Commission, is marked as doubtful (typically demarcated with double square brackets) or omitted altogether in most CT-based translations. This is a shame, because these verses contain some of the most powerful promises of Jesus, namely “these signs will follow those who believe: In My name they will cast out demons; they will speak with new tongues; they will take up serpents; and if they drink anything deadly, it will by no means hurt them; they will lay hands on the sick, and they will recover.” (Mark 16:17-18)

- Story of the Adulteress Woman (John 7:53-8:11) – The entire episode about the woman caught in adultery, with the famous lines “He who is without sin among you, let him throw a stone at her first” and “Neither do I condemn you; go and sin no more” is bracketed in CT-based translations (much like the end of Mark’s Gospel above). TR-based versions all include it as there are more than 900 manuscripts that all contain this passage.

- The “Johannine Comma” (1 John 5:7) – The explicit Trinitarian verse “For there are three that bear witness in heaven: the Father, the Word, and the Holy Spirit; and these three are one” is absent in CT manuscripts, even though the Greek grammar becomes awkward without it.

Other Differences in Modern Translations

Here is a quick (definitely non-exhaustive) compilation of various differences between the two traditions, followed by my quick commentary on why I think the differences matter:

- Romans 8:1 – The TR (NKJV) reads, “There is therefore now no condemnation to those who are in Christ Jesus, who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit.” CT-based versions omit the italicised phrase above. The omitted phrase fits the passage’s context; indeed, Romans 8:1-11 could be summarised as Paul’s detailed explanation of what it means to be “in Christ”, i.e. to walk not according to the flesh (the sinful nature) but instead to walk according to the Holy Spirit. Therefore, the TR reading of Romans 8:1 (which contains BOTH the phrase “in Christ Jesus” and “who do not walk according to the flesh, but according to the Spirit”) helpfully reinforces this teaching right at the beginning of the passage, preparing the reader.

- John 15:7 – The TR rendition reads, “If you abide in Me, and My words abide in you, you will ask what you desire, and it shall be done for you.” CT versions omit the phrase “you will”, so now the verse reads, “If you abide in Me, and My words abide in you, ask what you desire, and it shall be done for you.” Again, the variation is minor, but by omitting the phrase “you will”, this verse now misses the deep spiritual truth that God’s Word abiding in us transforms our very desires to align with His own will and causes us to ask in accordance with His will.

- Mark 9:29 “This kind can come out by nothing but prayer and fasting.” CT omits the phrase “and fasting”. More significantly, the parallel verse in Matthew 17:21 (“However, this kind does not go out except by prayer and fasting.”) is entirely missing in CT. Instead of explaining why I think this omission is unfortunate, I will refer the reader to this essay on fasting.

- 1 Timothy 4:12 – The phrase “in spirit” is missing in CT, weakening Paul’s exhortation to Timothy.

- Galatians 3:1 – CT removes “that you should not obey the truth” and “among you,” both of which add clarity and depth to Paul’s rebuke.

The pattern is clear: CT versions tend to omit phrases or even entire verses. Individually, these may seem small; but the cumulative effect of these omissions subtly weakens the richness of Scripture.

How Did This Happen?

The dividing line in manuscript history is the invention of the printing press. Erasmus, a brilliant scholar and devout Christian, compiled the best available Greek manuscripts into what became the Textus Receptus (Received Text) and had it published in 1516. Erasmus was fully aware of the existence of of Byzantine and Alexandrian groups of manuscripts in existence at the time, and clearly went with what he believed to have been the version that was faithfully transmitted generation after generation within the Church up to that point. And this TR text was used by Reformers and served as the basis for the Geneva Bible and later the KJV.

However, in the 19th century, two scholars, Westcott and Hort, believed they could reconstruct a more “original” New Testament by prioritising two early manuscripts: Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus. These manuscripts, discovered in Alexandria, differed significantly from the Byzantine tradition. The Codex Sinaiticus was literally discovered in a waste paper basket of the St Catherine monastery in Sinai peninsular in May 1844; apparently the manuscript was deemed by the Covent to be so full of faults that it was about to be burned. A 29-year-old German scholar Tischendorf managed to salvage some pages of this waste paper heap, giving us what we know to be Codex Sinaiticus. However, modern scholars such as Westcott and Hort, embracing Enlightenment rationalism, largely abandoned the TR in favour of this Critical Text, despite clear evidence that the Byzantine tradition was in continued use throughout Christendom ever since the early church until 19th century.

The Arian Heresy and Alexandrian Corruption

To understand the Byzantine-Alexandrian divide, we must go back to the 4th century. The Arian controversy denied the divinity of Christ, and many bishops—particularly in Alexandria—embraced this heresy. Some scholars argue that Alexandrian scribes altered texts to fit Arian theology, weakening references to Christ’s divinity. This would explain why modern CT-based translations tend to downplay key verses that affirm Jesus’ deity.

Contrast this with Athanasius, a young bishop who stood alone against Arianism, famously declaring: “If the whole world stands against the truth, then I stand against the world!” Through God’s grace, the Council of Nicaea upheld the deity of Christ, but the manuscript corruption remained. Even today, skeptics claim that early Christians did not believe Jesus was divine until Nicaea—a claim utterly disproven by archaeology, such as the 2024 Megiddo Mosaic (dated to 230 AD), which clearly refers to “God Jesus Christ.”

Why This Matters Today

Unfortunately, mainstream evangelical seminaries and publishers still favour the Critical Text. While the CT does not destroy core Christian doctrine, it is based on an academic methodology influenced by materialistic humanism rather than faith in God’s providential preservation of His Word.

This is why I recommend trying the NKJV. Unlike the KJV, which uses older English, the NKJV retains the TR manuscript base while providing footnotes to compare the TR, CT, and Majority Text (MT) differences. This allows readers to see the variations for themselves and judge their significance.

My Bible Journey

Like many evangelicals in the 1990s, I grew up with the NIV (1984) and later moved to the ESV, which I appreciated for its readability. I also used the NLT at times. However, two years ago, I decided to read through the NKJV, and my faith grew tremendously. Seeing the manuscript differences firsthand deepened my trust in God’s Word.

I also encourage reading a physical Bible rather than relying solely on apps. Marking notes, cross-referencing passages, and physically engaging with Scripture enhances comprehension and retention. I go through a new Bible every few years as my notes fill the margins, and I take the opportunity to try different translations.

Be Like Athanasius and Erasmus

Athanasius stood against the world for the truth of Christ’s divinity. Erasmus worked tirelessly to compile the most faithful text of the New Testament. We should follow their example and reject the materialistic skepticism that has crept into modern biblical scholarship.

Try reading a TR-based translation like the NKJV. You’ll thank me later.